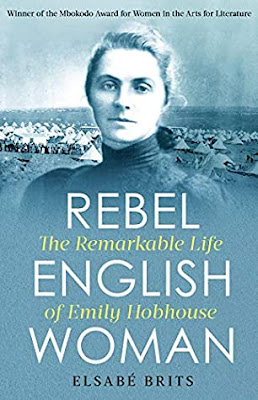

|

| Amazon |

Mention “concentration camps” and most people will immediately

think of the Nazis and places like Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau,

Ravensbruck and many others.

But once there were other concentration camps with very

British-sounding names such as Balmoral and Belfast, Howick and Nigel. There

was even one called America. These were located in South Africa during the Boer

War of 1899-1902.

These camps were imposed by the British, under the

command of Lord Kitchener, on the civilian population of South Africa.

Initially set up as “refugee” camps they soon deteriorated into squalid and

disease-infested open-air prisons. The numbers of women, children and elderly or sick men who died in tents in appalling conditions

vary depending on your choice of reference material and which statistics you

choose to believe, or whether they even bother to include the many thousands of

unknown innocent black and mixed race individuals who were also incarcerated in separate camps after being swept up in this now largely forgotten war. Officially, it is said at least 27,000 died, but the record-keeping is unreliable and the figure is more likely to be over 50,000.

Emily Hobhouse was the Englishwoman who first alerted the

world to the horror of these camps. For her efforts, she was labelled as “hysterical” and even a traitor. Although she did have the support of a small group of influential liberal friends, she was overwhelmingly vilified, despised and loathed in her

attempts to bring to light the conditions in the camps. In England and around the Empire no-one wanted to believe that the British were

capable of such inhumanity, especially towards the families of their enemy. When she tried to return to South Africa, she was deported.

Eventually, her actions did bear fruit and there was a softening in attitude although the hierarchy did not include Emily when the suffragist, Millicent Fawcett, headed up a commission of ladies to visit the camps for themselves and recommend improvements.

Emily made it her life’s purpose to promote the

rights of women and the cause of peace at all costs, and her actions are beautifully detailed in this magnificent biography by Elsabé Brits. With the aid of family archives hitherto unavailable to other biographers, the author reveals new information and delves deeply into the character of this committed and admirable woman.

Even after the Peace of Vereeniging in 1902, the camps

continued for a long time as Kitchener’s “scorched earth” policy meant there

were no homes or farms for many to return to. Her efforts to create work for

women and girls by way of introducing lace-making and spinning and weaving schools were

remarkable. In spite of poor health and diminished funds, Emily continued to

travel endlessly promoting peace and finding ways of helping those affected by

war.

During the First World War, she again embarrassed the British by flaunting European travel restrictions in order to liaise with senior Germans in attempts to organise a peace process, for which she was castigated severely and narrowly escaped imprisonment. After the war

was over, she organised food for thousands of Germans left to starve in

Leipzig.

In spite of her enormous humanitarian efforts and commitment to peace, even today she still remains a controversial character with some (mostly conservative

male) historians. Emily certainly had her faults in obstinacy and a refusal to compromise her

ethics and beliefs, but the best summation of her came from her friend General Jan Smuts, Prime Minister of South Africa:

"Let us not forget Emily Hobhouse. She was an Englishwoman to the marrow, proud of her people and its great mission and history. But for her patriotism was not enough. When she saw her country embark on a policy which was in conflict with the higher moral law, she did not say: ‘My country, right or wrong.’ She wholeheartedly took our side against that of her own people, and in doing so rendered an imperishable service, not only to us, but also to her own England and to the world at large.

For this loyalty to the higher and great things of life she suffered deeply. Her action was not understood or appreciated by her own people … Emily Hobhouse will stand out … as a trumpet call to the higher duty … and loyalty to the great things which … bind together all nations as a great spiritual brotherhood …"

Today, Emily is still revered by descendants of the

Boer women and children she strove to help and after she died in 1926, her

ashes were buried at the base of the National Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein.

A five star biography about a five star woman.

|

| Detail - National Women's Monument, Bloemfontein (Emily Hobhouse witnessed this very scene and worked with the sculptor in its design.) |